Download the PHP package mindplay/unbox without Composer

On this page you can find all versions of the php package mindplay/unbox. It is possible to download/install these versions without Composer. Possible dependencies are resolved automatically.

Download mindplay/unbox

More information about mindplay/unbox

Files in mindplay/unbox

Package unbox

Short Description Fast, simple, easy-to-use DI container

License LGPL-3.0+

Informations about the package unbox

Unbox is a opinionated dependency injection container, with a gentle learning curve.

Compatible with PSR-11.

To upgrade from an older (pre-3.x) version, please see the upgrade guide.

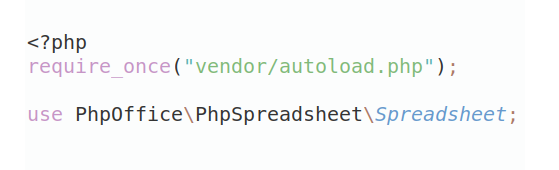

Installation

With Composer: require mindplay/unbox

Introduction

This library implements a dependency injection container with a very small footprint, a small number of concepts and a reasonably short learning curve, good performance, and quick and easy configuration relying mainly on the use of closures for IDE support.

The container is capable of resolving constructor arguments, often automatically, with as little

configuration as just the class-name. It will also resolve arguments to any callable, including

objects that implement __invoke(). It can also be used as a generic factory class, capable of

creating any object for which the constructor arguments can be resolved - the common use-case

for this is in your own factory classes, e.g. a controller factory or action dispatcher.

Quick Overview

Below, you can find a complete guide and full documentation - but to give you an idea of what this library does, let's open with a quick code sample.

For this basic example, we'll assume you have the following related types:

Unbox has a two-stage life-cycle. The first stage is the creation of a ContainerFactory - this

class provides bootstrapping and configuration facilities. The second stage begins with a call

to ContainerFactory::createFactory() which creates the actual Container instance, which

provides the facilities enabling client-code to invoke functions and constructors, etc.

Let's bootstrap a ContainerFactory with those dependencies, in a "bootstrap" file somewhere:

Then configure the missing $cache_path for the cache component, add that to a "config" file somewhere:

Now that the ContainerFactory is fully bootstrapped, we're ready to create a Container:

In this simple example, we're now done with ContainerFactory, which can simply fall out of

scope. (In more advanced scenarios, such as long-running React or

PHP-PM applications, you might want to maintain a

reference to ContainerFactory, so you can create a fresh Container for each request.)

You can now take your UserRepository out of the Container, either by asking for it directly:

Or, by using a type-hinted closure for IDE support:

To round off this quick example, let's say you have a controller:

Using the container as a factory, you can create an instance of any controller class:

Finally, you can dispatch the show() action, with dependency injection - as a naive example,

we're simply going to inject $_GET directly as parameters to the method:

Using $_GET as parameters to the call, the $user_id argument to UserController:show() will

be resolved as $_GET['user_id'].

That's the quick, high-level overview.

API

If you're already comfortable with dependency injection, and just want to know what the API looks

like, below is a quick overview of the ContainerFactory API:

The following provides a quick overview of the Container API:

If you're new to dependency injection, or if any of this baffles you, don't panic - everything is covered in the guide below.

Terminology

The following terminology is used in the documentation below:

-

Callable: refers to the

callablepseudo-type as defined in the PHP manual. -

Component: any object or value registered in a container, whether registered by class-name, interface-name, or some other arbitrary name.

-

Singleton: when we say "singleton", we mean there's only one component with a given name within the same container instance; of course, you can have multiple container instances, so each component is a "singleton" only within the same container.

- Dependency: in our context, we mean any registered component that is required by another component, by a constructor (when using the container as a factory) or by any callable.

Dependency Resolution

Any argument, whether to a closure being manually invoked, or to a constructor being automatically invoked as part of resolving a longer chain of dependencies, is resolved according to a consistent set of rules - in order of priority:

-

If you provide the argument yourself, e.g. when registering a component (or configuration function, or when invoking a callable) this always takes precedence. Arguments can include boxed values, such as (typically) references to other components, and these will be unboxed as late as possible.

-

Type-hints is the preferred way to resolve singletons, e.g. types of which you have only one instance (or one "preferred" instance) in the same container. Singletons are usually registered under their class-name, or interface-name, or sometimes both.

-

Parameter names, e.g. components matching the precise argument name (without

$) - this works only when it's safe, which it is in most cases, the only exception being constructors invoked viacreate()where component names in the Container happen to match parameter names in the constructor. (constructor arguments given via the$maparguments are of course safe, too.) - A default parameter value, if provided, will be used as a last resort - this can be useful

in cases such as

function ($db_port = 3306) { ... }, which allows for optional configuration of simple values with defaults.

For dependencies resolved using type-hints, the parameter name is ignored - and vice-versa: if a dependency is resolved by parameter name, the type-hint is ignored, but will of course be checked by PHP when the function/method/constructor is invoked. Note that using type-hints either way is good practice (when possible) as this provides self-documenting configurations with IDE support.

Guide

In the following sections, we'll assume that a ContainerFactory instance is in scope, e.g.:

Bootstrapping

The most commonly used method to bootstrap a container is register() - this is the method

that lets you register a component for dependency injection.

This method generally takes one of the following forms:

Where:

$nameis a component name$typeis a fully-qualified class-name$mapis a mixed list/map of parameters (see below)$funcis a custom factory function

When $type is used without $name, the component name is assumed to also be the name

of the type being registered.

The $map argument is mixed list and/or map of parameters. That is, if you include

parameters without keys (such as ['apple', 'pear']) these are taken as being positional

arguments, while parameters with keys (such as ['lives' => 9]) are matched against

the parameter name of the callable or constructor being invoked.

When supplying custom arguments via $map, it is common to use $factory->ref('name')

to obtain a "boxed" reference to a component - when the registered component is created

(on first use) any "boxed" arguments will be "unboxed" at that time. In other words, this

enables you to supply other components as arguments "lazily", without activating them

until they're actually needed.

If the callable $func is supplied, this is registered as your custom component creation

function - dependency injection is done for this closure, so this is usually the best way

to specify how a component should be created, if you care about IDE support. (You should!)

Examples

The following examples are all valid use-cases of the above forms:

-

register(Foo::class)registers a component by it's class-name, and will try to automatically resolve all of it's constructor arguments. -

register(Foo::class, ['bar'])registers a component by it's class-name, and will use'bar'as the first constructor argument, and try to resolve the rest. -

register(Foo::class, [$factory->ref(Bar::class)])creates a boxed reference to a registered componentBarand provides that as the first argument. -

register(Foo::class, ['bat' => 'zap'])registers a component by it's class-name and will use'zap'for the constructor argument named$bat, and try to resolve any other arguments. -

register(Bar::class, Foo::class)registers a componentFoounder another nameBar, which might be an interface or an abstract class. -

register(Bar::class, Foo::class, ['bar'])same as above, but uses'bar'as the first argument. -

register(Bar::class, Foo::class, ['bat' => 'zap'])same as above, but, well, guess. -

register(Bar::class, function (Foo $foo) { return new Bar(...); })registers a component with a custom factory function. register(Bar::class, function ($name) { ... }, [$factory->ref('db.name')]);registers a component creation function with a reference to a component "db.name" as the first argument.

In effect, you can think of $func as being an optional argument.

The provided parameter values may include any BoxedValueInterface, such as (commonly) the boxed

component reference created by ContainerFactory::ref() - these will be unboxed as late as possible.

Aliasing

Sometimes you need to register the same component under two different names - one common use-case, is to register the same component both for a concrete and abstract type, e.g. for a class and an interface.

For example, it's ordinary to register a cache component twice:

Using an alias, in this example, means that "db.cache" by default will resolve as

CacheInterface, but gives us the ability to override the definition of

"db.cache" with a different implementation, without affecting other components which

might also be using CacheInterface as a default.

Direct Insertion

Not all dependencies are expensive to create - simple values (such as host-names and port-numbers)

do not benefit from deferred initialization with register(), and instead should be inserted

into the container directly:

Another common use-case for set() is to inject objects for which you can't defer creation.

Overrides

To override an existing component, simply call register() with an already-registered

component name - this will completely replace an existing component definition.

Note that overriding a component does not affect any registered configuration functions - it is therefore important that, if you do override a component, the new component must be compatible with the replaced component. Configuration in general is covered below.

Configuration

To perform additional configuration of a registered component, use the configure() method.

This method takes one of the following forms:

Where:

$nameis the name of a component being configured$funcis a function that configures the component in some way$mapis a mixed list/map of parameters (as explained above)

The callable $func will be called with dependency injection - the first argument of

this function is the component being configured; you should type-hint it (if possible, for

IDE support) although you're not strictly required to. Any additional arguments will be

resolved as well.

The optional array $map is a mixed list/map of parameters, as covered above.

If no $name is supplied, the first argument from the given $func is used to infer the

component name from the type-hint.

As an example, let's say you've configured a PDO component:

In a configuration file, simple values like $db_host can be inserted directly, e.g. with

$factory->set("db_host", "localhost") - but suppose you need to do something after

the connection is created? Here's where configure() comes into play:

Note that, in this example, configure() will infer the component name "PDO" from the

type-hint - in a scenario with multiple named PDO instances, you must explicitly specify

the component name as the first argument, e.g.:

Property or Setter Injection

This library doesn't support neither property nor setter injection, but both can be accomplished

by just doing those things in a call to configure() - for example:

In this example, upon first use of Connection, a dependency LoggerInterface will be

unboxed and injected via setter-injection. (We believe this approach is much safer than

offering a function that accepts the method-name as an argument - closures are more powerful,

much safer, and provide full IDE support, inspections, automated refactoring, etc.)

Modification

You can use configure() to modify values (such as strings, numbers or arrays) in the container.

For example, let's say you have a middleware stack defined as an array:

If you need to append to the stack, you can do this:

Note the return statement - this is what causes the value to get updated in the container.

Decoration

The decorator pattern is another pattern

that can be implemented with configure() - for example, lets say you bootstrapped your

container with a product repository implementation and interface:

Now lets say you implement a cached product repository decorator - you can bootstrap this by creating and returning the decorator instance like this:

Note that, when replacing components in this manner, of course you must be certain that the replacement has a type that can pass a type-check in the recipient constructor or method.

Packaged Providers

You can package a set of register() and configure() calls for convenient reuse, by

implementing ProviderInterface - for example:

You can then easily bootstrap your projects with providers, e.g.:

Providers of course can also call ContainerFactory::add() to bootstrap other providers - with

this in mind, you can make e.g. development or production setup for your app as easy as

calling e.g. $container->add(new DevelopmentProvider) to provide complete bootstrapping

for a quick development setup. Even if somebody wanted to override some of the registrations

in e.g. your default development setup, they can of course still do that, e.g. by calling

register() again to override components as needed.

Provider Requirements

In large, modular architectures, you may have many Providers with inter-dependencies, which can become difficult to manage at scale.

Since Providers exist outside the realm of the Container, the concept of Requirements can

be used to define verifiable provider interdependencies, which will be checked at the time

when createContainer() is called.

Requirements may be defined by calling requires(), and more than one Provider may specify the

same Requirement - possibly for different reasons, which may be described using the optional

$description argument.

Requirements may be fulfilled by calling either register() or provides().

Component Requirements

Providers may depend on the consumer to manually register a component.

For example, the following Provider requires you to register a PDO connection instance:

Attempting to bootstrap this Provider, without manually registering the PDO instance, will

generate an Exception, as soon as createContainer() is called - which is much easier to debug

than the NotFoundException you would otherwise get, and which might not occur until you try

to resolve a component that actually depends on the database connection.

Abstract Requirements

Providers may have abstract Requirements - something that can't be expressed by a simple component dependency.

For example, the following Provider requires you to simply indicate that you've bootstrapped a "payment gateway" - whatever that means to the Provider in question:

Another provider needs to explicitly indicate fulfillment of this abstract Requirement:

Note that abstract Requirements should be a last resort - component dependencies are generally simpler and easier to understand. This feature exists primarily to support complex, large-scale modular frameworks.

Fallback Containers

You can use this feature to build layered architecture with different component life-cycles.

Note that this type of architecture is less about reuse (which in most cases could be achieved more simply by just reusing providers) and more about separating dependencies into architectural layers.

The most common use-case for this feature is in long-running "daemons", such as web-hosts, where this feature can be used to achieve separation of short-lived, request-specific components from long-lived services. For example, controllers or session-models might be registered in containers that get created and disposed with each request - while a database connection or an SMTP client might be registered in a single fallback container that exists for as long as the application is running, eliminating redundant start-up overhead.

This kind of separation is also useful in terms of architecture, where it forces you to be deliberate and aware of dependencies on request-specific components, since these will not be available in the long-lived container. Similarly, maybe your project has a console-based front-end as well, where this type of architecture can be used to ensure your command-line dependencies are not available to the components of your web-host - and so on.

In practical terms, to register a fallback container, use the registerFallback method on

a ContainerFactory instance. Containers created by a factory with one or more registered

fallbacks, will internally query fallbacks (in the order they were added) for any components

that haven't been registered in the container itself - effectively, this means that calls

to has and get will propagate to any registered fallback containers.

A typical approach is to register the container factory for short-lived services as a component in the long-lived main service container - for example:

With this bootstrapping in place, you can now create instances of the request-context container

as needed, e.g. in a long-lived component that handles incoming web-requests:

When the $request_container falls out of scope, any short-lived components such as the LoginController

will be released along with the container - while any long-lived components such as DatabaseConnection

will remain in the $app_container, with the same instance being passed to every new instance of the

controller.

Using Containers

Obtaining the contents of a container by simply pulling components out of it can seem very convenient, and is therefore tempting - but usually wrong! You should inform yourself about the difference and avoid using the container as a service locator.

Rule of Thumb:

Never use a Container to look up a component's own direct dependencies.

Conversely, using a Container to look up dependencies on behalf of other components is usually okay.

In the following sections, we'll assume that a Container instance is in scope, e.g.:

The most basic form of component access, is a direct lookup:

The more indirect form of component access, is an indirect lookup, by resolving parameters:

The result in these two examples, is the same - but it's important to note that, in the call()

example, the two arguments are being resolved in two different ways: the CacheInterface param

is resolved by class-name, whereas the $db_name param is being resolved by parameter name.

The latter only works because the $db_name component is registered under that precise name -

if it had been registered under a name such as "db.name", the container would be unable to

resolve this argument automatically; instead, you would have had to write:

Note that call() will accept any type of callable.

Factory Facet

The create() method can be used to invoke a constructor, to create an instance of any

class, on demand.

An important thing to understand, is that e.g. register() and configure() have no

bearing on this functionality - the purpose of this method, is to create instance of types

that aren't registered as components in the container, but (likely) have dependencies

which can be provided by the container.

Controllers are a great example - you most likely don't want to register every individual controller class as a component in the container; rather, you probably want a controller factory, capable of creating any controller.

As an example, here's a simple implementation of a controller factory that resolves the

typical "foo/bar" route string as e.g. FooController::bar() - like so:

Note the FactoryInterface type-hint in the constructor - in situations where you only

care about using the container as a factory, you should type-hint against this facet.

Inspection

You can inspect the state of components in a container using has() and isActive().

To check if a component is defined, use has() - for example:

Whether a component is directly inserted with set(), or defined using register(), the

has() method will return true.

To check if a component has been activated, use isActive() - for example:

A component is considered "active" when it has been used for the first time - components

may get activated directly by calls to get(), or may get indirectly activated by

cascading activation of dependencies.

Opinionated

Less is more. We support only what's actually necessary to create beautiful architecture - we do not provide a wealth of "convenience" features to support patterns we wouldn't use, or patterns that aren't very common and can easily be implemented with the features we do provide.

Features:

-

Productivity-oriented - favoring heavy use of closures for full IDE support: refactoring-friendly definitions with auto-complete support, inspections and so on.

-

Performance-oriented only to the extent that it doesn't encumber the API.

-

Versatile - supporting many different options for registration and configuration using the same, low number of public methods, including value modifications, decorators, etc.

-

Zero configuration - we don't include any optional features or configurable behavior: the container always behaves consistently, with the same predictable performance and interoperability.

- PHP 5.5+ for

::classsupport, and because you really shouldn't be using anything older.

Non-features:

-

NO annotations - because sprinkling bits of your container configuration across your domain model is a really terrible idea.

-

NO auto-wiring - because

$container->register(Foo::name)isn't a burden, and explicitly designates something as being a service; unintentionally treating a non-singleton as a singleton can be a weird experience. -

NO caching - because configuring a container really shouldn't be so much overhead as to justify the need for caching. Unbox is fast.

-

NO property/setter injections because it blurs your dependencies - use constructor injection, and for optional dependencies, use optional constructor arguments; you don't, after all, need to count the number of arguments anymore, since everything will be injected. (if you do have a good reason to inject something via properties or setters, you can do that from inside a closure, in a call to

configure(), with full IDE support.) -

NO syntax - we don't invent or parse any special string syntax, anywhere, period. Any problem that can be solved with custom syntax can also be solved with clean, simple PHP code.

-

No chainable API, because call chains (in PHP) don't play nice with source-control.

- All registered components are singletons - we do not support factory registrations; if you need to register a factory, the proper way to do that, is to either implement an actual factory class (which is usually better in the long run), or register the factory closure itself as a named component.

Benchmark

This is not intended as a competitive benchmark, but more to give you an idea of the performance implications of choosing from three very different DI containers with very different goals and different qualities - from the smallest and simplest to the largest and most ambitious:

-

pimple is as simple as a DI container can get, with absolutely no bell and whistles, and barely any learning curve, totalling around 250 LOC.

-

unbox with just a few classes and interfaces - more concepts and a bit more learning curve than pimple, totalling around 350 LOC.

- php-di is a pristine dependency injection framework with all the bells and whistles - rich with features, but also has more concepts and learning curve, more overhead, and totalling around 3000 LOC.

The included simple benchmark generates the following benchmark results on a WSL2 under Windows 11 with PHP 8.2.10.

Time to configure the container:

unbox: configuration ............................. 0.006 msec ....... 41.78% ......... 1.00x

pimple: configuration ............................ 0.008 msec ....... 51.25% ......... 1.23x

php-di: configuration ............................ 0.013 msec ....... 89.02% ......... 2.13x

php-di: configuration [compiled] ................. 0.015 msec ...... 100.00% ......... 2.39xTime to resolve the dependencies in the container, on first access:

pimple: 1 repeated resolutions ................... 0.002 msec ........ 9.14% ......... 1.00x

php-di: 1 repeated resolutions [compiled] ........ 0.004 msec ....... 18.88% ......... 2.06x

unbox: 1 repeated resolutions .................... 0.006 msec ....... 26.47% ......... 2.90x

php-di: 1 repeated resolutions ................... 0.022 msec ...... 100.00% ........ 10.94xTime for multiple subsequent lookups:

pimple: 3 repeated resolutions ................... 0.003 msec ....... 11.44% ......... 1.00x

php-di: 3 repeated resolutions [compiled] ........ 0.004 msec ....... 18.55% ......... 1.62x

unbox: 3 repeated resolutions .................... 0.006 msec ....... 27.24% ......... 2.38x

php-di: 3 repeated resolutions ................... 0.023 msec ...... 100.00% ......... 8.74x

pimple: 5 repeated resolutions ................... 0.003 msec ....... 13.36% ......... 1.00x

php-di: 5 repeated resolutions [compiled] ........ 0.005 msec ....... 19.68% ......... 1.47x

unbox: 5 repeated resolutions .................... 0.007 msec ....... 28.02% ......... 2.10x

php-di: 5 repeated resolutions ................... 0.023 msec ...... 100.00% ......... 7.48x

pimple: 10 repeated resolutions .................. 0.004 msec ....... 17.48% ......... 1.00x

php-di: 10 repeated resolutions [compiled] ....... 0.005 msec ....... 22.15% ......... 1.27x

unbox: 10 repeated resolutions ................... 0.007 msec ....... 29.83% ......... 1.71x

php-di: 10 repeated resolutions .................. 0.024 msec ...... 100.00% ......... 5.72x