Download the PHP package hindy/template without Composer

On this page you can find all versions of the php package hindy/template. It is possible to download/install these versions without Composer. Possible dependencies are resolved automatically.

Download hindy/template

More information about hindy/template

Files in hindy/template

Package template

Short Description Fast PHP templating engine

License MIT

Informations about the package template

Flow - Fast PHP Templating Engine

Introduction

Flow began life as a major fork of the original Twig templating engine by Armin Ronacher, which he made for Chyrp, a blogging engine. Flow features template inheritance, includes, macros, custom helpers, autoescaping, whitespace control and many little features that makes writing templates enjoyable. Flow tries to give a consistent and coherent experience in writing clean templates. Flow compiles each template into its own PHP class; used with APC, this makes Flow a very fast and efficient templating engine. Templates can be read from files, loaded from string arrays, or even from databases with relative ease.

Installation

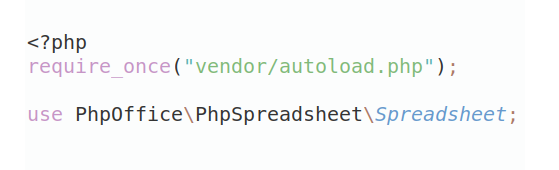

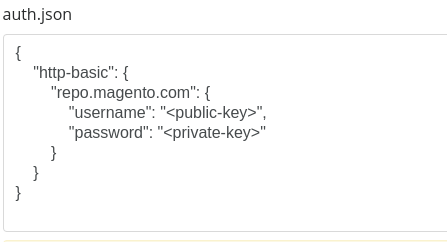

The easiest way to install is by using Composer; the minimum composer.json configuration is:

Flow requires PHP 5.3 or newer. PHP 5.4 is strongly recommended.

Usage

Using Flow in your code is straight forward:

The Loader constructor accepts an array of options. They are:

source: Path to template source files.target: Path to compiled PHP files.mode: Recompilation mode.mkdir: Mode to pass tomkdir()when the target directory doesn't exist. Usefalseto suppress automatic target directory creation. Defaults to 0777.adapter: OptionalFlow\Adapterobject. See the section on loading templates from other sources near the bottom of this document.helpers: Array of custom helpers.

The source and target options are required.

The mode option can be one of the following:

Loader::RECOMPILE_NEVER: Never recompile an already compiled template.Loader::RECOMPILE_NORMAL: Only recompile if the compiled template is older than the source file due to modifications.Loader::RECOMPILE_ALWAYS: Always recompile whenever possible.

The default mode is Loader::RECOMPILE_NORMAL. If a template has never been

compiled, or the compiled PHP file is missing, the Loader will compile it once

regardless of what the current mode is.

In a typical development environment, the Loader::RECOMPILE_NORMAL mode should

be used, while the Loader::RECOMPILE_NEVER mode should be used for production

whenever possible. The Loader::RECOMPILE_ALWAYS mode is used only for internal

debugging purposes by the developers and should generally be avoided.

Two kinds of exceptions are thrown by Flow: SyntaxError for syntax errors, and

RuntimeException for everything else.

Any reference to template files outside the source directory is considered to

be an error.

Syntax checking

Syntax checking can be done as following:

The above example will check the template for errors without actually compiling it.

Compiling programatically

It is possible to compile templates without loading and displaying them:

This is useful if your application needs to bulk-compile several templates or allows users to upload, create, or modify templates.

Basic concepts

Flow uses {% and %} to delimit block tags. Block tags are used mainly

for block declarations in template inheritance and control structures. Examples

of block tags are block, for, and if. Some block tags may have a body

segment. They're usually enclosed by a corresponding end<tag> tag. Flow uses

{{ and }} to delimit output tags, and {# and #} to delimit comments.

Keywords and identifiers are case-sensitive.

Comments

Use {# and #} to delimit comments:

{# This is a comment. It will be ignored. #}Comments may span multiple lines but cannot be nested; they will be completely removed from the resulting output.

Expression output

To output a literal, variable, or any kind of expression, use the opening {{

and the closing }} tags:

Hello, {{ username }}

{{ "Welcome back, " ~ username }}

{{ "Two plus two equals " ~ 2 + 2 }}Literals

There are several types of literals: numbers, strings, booleans, arrays, and

null.

Numbers

Numbers can be integers or floats:

{{ 42 }} and {{ 3.14 }}Large numbers can be separated by underscores to make it more readable:

Price: {{ 12_000 | number_format }} USDThe exact placing of is insignificant, although the first character must be a digit; any character inside numbers will be removed. Numbers are translated into PHP numbers and thus are limited by how PHP handles numbers with regards to upper/lower limits and precision. Complex numeric and monetary operations should be done in PHP using the GMP extension or the bcmath extension instead.

Strings

Strings can either be double quoted or single quoted; both recognize escape sequence characters. There are no support for variable extrapolation. Use string concatenation instead:

{{ "This is a string " ~ 'This is also a string' }}You can also join two or more strings or scalars using the join operator:

{{ "Welcome," .. user.name }}The join operator uses a single space character to join strings together.

Booleans

{{ true }} or {{ false }}When printed or concatenated, true will be converted to 1 while false will

be converted to an empty string. This behavior is consistent with the way PHP

treats booleans in a string context.

Arrays

{{ ["this", "is", "an", "array"][0] }}Arrays are also hash tables just like in PHP:

{{ ["foo" => "bar", 'oof' => 'rab']['foo'] }}Printing arrays will cause a PHP notice to be thrown; use the join helper:

{{ [1,2,3] | join(', ') }}Nulls

{{ null }}When printed or concatenated, null will be converted to an empty string. This

behavior is consistent with the way PHP treats nulls in a string context.

Operators

In addition to short-circuiting, boolean operators or and and returns one

of their operands. This means you can, for example, do the following:

Status: {{ user.status or "default value" }}Note that the strings '0' and '' are considered to be false. See the section

on branching for more information. This behavior is consistent with the way PHP

treats strings in a boolean context.

Comparison operators can take multiple operands:

{% if 1 <= x <= 10 %}

<p>x is between 1 and 10 inclusive.</p>

{% endif %}Which is equivalent to:

{% if 1 <= x and x <= 10 %}

<p>x is between 1 and 10 inclusive.</p>

{% endif %}The in operator works with arrays, iterators and plain objects:

{% if 1 in [1,2,3] %}

1 is definitely in 1,2,3

{% endif %}

{% if 1 not in [4,5,6] %}

1 is definitely not in 4,5,6

{% endif %}For iterators and plain objects, the in operator first converts them using a

simple (array) type conversion.

Use ~ (tilde) to concatenate between two or more scalars as strings:

{{ "Hello," ~ " World!" }}String concatenation has a lower precedence than arithmetic operators:

{{ "1 + 1 = " ~ 1 + 1 ~ " and everything is OK again!" }}Will yield

1 + 1 = 2 and everything is OK again!Use .. (a double dot) to join two or more scalars as string using a single

space character:

{{ "Welcome," .. user.name }}String output, concatenations and joins coerce scalar values into strings.

Operator precedence

Below is a list of all operators in Flow sorted and listed according to their precedence in descending order:

- Attribute access:

.and[]for objects and arrays - Filter chaining:

| - Arithmetic: unary

-and+,%,/,*,-,+ - Concatenation:

..,~ - Comparison:

!==,===,==,!=,<>,<,>,>=,<= - Conditional:

in,not,and,or,xor - Ternary:

? :

You can group subexpressions in parentheses to override the precedence rule.

Attribute access

Objects

You can access an object's member variables or methods using the . operator:

{{ user.name }}

{{ user.get_full_name() }}When calling an object's method, the parentheses are optional when there are no arguments passed. The full semantics of object attribute access are as follows:

For attribute access without parentheses, in order of priority:

- If the attribute is an accessible member variable, return its value.

- If the object implements

__get, invoke and return its value. - If the attribute is a callable method, call and return its value.

- If the object implements

__call, invoke and return its value. - Return null.

For attribute access with parentheses, in order of priority:

- If the attribute is a callable method, call and return its value.

- If the object implements

__call, invoke and return its value. - Return null.

You can always force a method call by using parentheses.

Arrays

You can return an element of an array using either the . operator or the [

and ] operator:

{{ user.name }} is the same as {{ user['name'] }}

{{ users[0] }}The . operator is more restrictive: only tokens of name type can be used as

the attribute. Tokens of name type begins with an alphabet or an underscore and

can only contain alphanumeric and underscore characters, just like PHP variables

and function names.

One special attribute access rule for arrays is the ability to invoke closure functions stored in arrays:

And call the fullname "method" in the template as follows:

{{ user.fullname }}When invoked this way, the closure function will implicitly be passed the array it's in as the first argument. Extra arguments will be passed on to the closure function as the second and consecutive arguments. This rule lets you have arrays that behave not unlike objects: they can access other member values or functions in the array.

Dynamic attribute access

It's possible to dynamically access an object or array attributes:

{% set attr = 'name' %}

Your name: {{ user[attr] }}Helpers

Helpers are simple functions you can use to test or modify values prior to use. There are two ways you can use them:

- Using helpers as functions

- Using helpers as filters

Except for a few exceptions, they are exchangeable.

Using helpers as functions

{{ upper(title) }}You can chain helpers just like you can chain function calls in PHP:

{{ nl2br(upper(trim(my_data))) }}Using helpers as filters

Use the | character to separate the data with the filter:

{{ title | upper }}You can use multiple filters by chaining them with the | character. Using them

this way is not unlike using pipes in Unix: the output of the previous filter is

the input of the next one. For example, to trim, upper case and convert newlines

to <br> tags (in that order), simply write:

{{ my_data | trim | upper | nl2br }}Some built-in helpers accept additional parameters, delimited by parentheses and separated by commas, like so:

{{ "foo " | repeat(3) }}Which is equivalent to the following:

{{ repeat("foo ", 3) }}When using helpers as filters, be careful when mixing operators:

{{ 12_000 + 5_000 | number_format }}Due to operator precedence, the above example is semantically equivalent to:

{{ 12_000 + (5_000 | number_format) }}Which, when compiled to PHP, will output 12005 which is probably not what you'd expect. Either put the addition inside parentheses like so:

{{ (12_000 + 5_000) | number_format }}Or use the helper as a function:

{{ number_format(12_000 + 5_000) }}Special raw helper

The raw helper can only be applied as a filter. Its sole purpose is to mark an

expression as a raw string that will not be escaped even when autoescaping is

turned on:

{% autoescape on %}

{{ "<p>this is a valid HTML paragraph</p>" | raw }}Without the raw filter being applied, the above will yield

<p>this is a valid HTML paragraph</p>Built-in helpers

abs, bytes, capitalize, cycle, date, dump, e, escape, first,

format, is_divisible_by, is_empty, is_even, is_odd, join,

json_encode, keys, last, length, lower, nl2br, number_format,

range, raw, repeat, replace, strip_tags, title, trans, trim,

truncate, unescape, upper, url_encode, word_wrap.

Registering custom helpers

Registering custom helpers is straightforward:

You can use your custom helpers just like any other built-in helpers:

A random number: {{ random() }} is truly {{ "bizarre" | exclamation }}When used as functions, the parentheses are necessary even if your helpers do not take any parameters. As a rule, when used as a filter, the input is passed on as the first argument to the helper. It's advisable to have a default value for every parameter in your custom helper.

Since built-in helpers and custom helpers share the same namespace, you can override built-in helpers with your own version although it's generally not recommended.

Branching

Use the if tag to branch. Use the optional elseif and else tags to have

multiple branches:

{% if expression_1 %}

expression 1 is true!

{% elseif expression_2 %}

expression 2 is true!

{% elseif expression_3 %}

expression 3 is true!

{% else %}

nothing matches!

{% endif %}Values considered to be false are false, null, 0, '0', '', and []

(empty array). This behavior is consistent with the way PHP treats data types in

a boolean context. From experience, it's generally useful to have the string

'0' be considered a false value: usually the data comes from a relational

database which, in most drivers in PHP, integers in returned tuples are

converted to strings. You can always use the strict === and !== comparison

operators.

Inline if and unless statement modifiers

Apart from the standalone block tag version, the if tag is also available as

a statement modifier. If you know Ruby or Perl, you might find this familiar:

{{ "this will be printed" if this_evaluates_to_true }}The above is semantically equivalent to:

{%- if this_evaluates_to_true -%}

{{ "this will be printed" }}

{%- endif -%}You can use any kind of boolean logic just as in the standard block tag version:

{{ "this will be printed" if not this_evaluates_to_false }}Using the unless construct might be more natural for some cases.

The following is equivalent to the above:

{{ "this will be printed" unless this_evaluates_to_false }}Inline if and unless modifiers are available for output tags, break and continue tags, extends tags, parent tags, set tags, and include tags.

Ternary operator ?:

You can use the ternary operator if you need branching inside an expression:

{{ error ? '<p>' ~ error ~ '</p>' : '<p>success!</p>' }}The ternary operator has the lowest precedence in an expression.

Iteration

Use the for tag to iterate through each element of an array or iterator. Use

the optional else clause to implicitly branch if no iteration occurs:

{% for link in links %}

<a href="{{ link.url }}">{{ link.title }}</a> {% else %}

{% else %}

There are no links available.

{% endfor %}Empty arrays or iterators, and values other than arrays or iterators will branch

to the else or empty clause.

You can also iterate as key and value pairs by using a comma:

{% for key, value in associative_array %}

<p>{{ key }} = {{ value }}</p>

{% endfor %}Both key and value in the example above are local to the iteration. They

will retain their previous values, if any, once the iteration stops.

The special variable loop contains several useful attributes and is available

for use inside the for block:

{% for user in users %}

{{ user }}{{ ", " unless loop.last }}

{% endfor %}If you have an ordinary loop variable, its value will temporarily be out of

scope inside the for block.

The special loop variable has a few attributes:

loop.counter0,loop.index0: The zero-based index.loop.counter,loop.index: The one-based index.loop.revindex0: The zero-based reverse index.loop.revindex: The one-based reverse indexloop.first: Evaluates totrueif the current iteration is the first.loop.last: Evaluates totrueif the current iteration is the last.loop.parent: The parent iterationloopobject if applicable.

Break and continue

You can use break and continue to break out of a loop and to skip to the

next iteration, respectively. The following will print "1 2 3":

{% for i in [0,1,2,3,4,5] %}

{% continue if i < 1 %}

{{ i }}

{% break if i > 2 %}

{% endfor %}Set

It is sometimes unavoidable to set values to variables and object or array

attributes; use the set construct:

{% set fullname = user.firstname .. user.lastname %}

{% set user.fullname = fullname %}You can also use set as a way to buffer output and store the result in a

variable:

{% set slogan %}

<p>This changes everything!</p>

{% endset %}

...

{{ slogan }}

...The scope of variables introduced by the set construct is always local to its

surrounding context.

Blocks

Blocks are at the core of template inheritance:

{# this is in "parent_template.html" #}

<p>Hello</p>

{% block content %}

<p>Original content</p>

{% endblock %}

<p>Goodbye</p>

{# this is in "child_template.html" #}

{% extends "parent_template.html" %}

This will never be displayed!

{% block content %}

<p>This will be substituted to the parent template's "content" block</p>

{% endblock %}

This will never be displayed!When child_template.html is loaded, it will yield:

<p>Hello</p>

<p>This will be substituted to the parent template</p>

<p>Goodbye</p>Block inheritance works by replacing all blocks in the parent, or extended template, with the same blocks found in the child, or extending template, and using the parent template as the layout template; the child template layout is discarded. This works recursively upwards until there are no more templates to be extended. Two blocks in a template cannot have the same name. You can define blocks within another block, but not within macros.

Extends

The extends construct signals Flow to load and extend a template. Blocks

defined in the current template will override blocks defined in extended

templates:

{% extends "path/to/layout.html" %}The template extension mechanism is fully dynamic with some caveats. You can use context variables or wrap it in conditionals just like any other statement:

{% extends layout if some_condition %}You can also use the ternary operator:

{% extends some_condition ? custom_layout : "default_layout.html" %}You cannot however use expressions and variables that are calculated inside the

template before the extends tag. This is because the extends tag is the first

thing a template will evaluate regardless of where its position is in the

template. This is also why it's best to put your extends tags somewhere at the

top of your templates. For example, the following will not work:

{% set extend_template = true %}

{% extends "parent.html" if extend_template %}The following will also not work because tpl is a value calculated inside the

template before the extends tag:

{% set tpl = "parent.html" %}

{% extends tpl %}If however the extend_template or the tpl variables are context variables

that already exist before the template loads, then the two examples above will

work as expected.

It is a syntax error to declare more than one extends tag per template or to

declare an extends tag anywhere but at the top level scope.

Parameterized template extension

Using the set tag to override a context variable before extending a parent

template will not work. This is because an extends tag is the first thing a

template will evaluate regardless of where its position is in the template and

extending a template will discard the current extending template's layout (i.e.,

everything outside block tags) in favor of the extended template's layout.

You can however pass an array to override a parent template's context when extending it. With a parent template:

{# this is in parent.html #}

{% if show %}

TADA!

{% endif %}And a child template:

{# this is in child.html #}

{% extends "parent.html" with ['show' => true] %}Rendering the child template will produce:

TADA!Likewise, you can't use variables created using the set tag inside the array

parameter used with the extends tag. For example, the following will not work:

{% set foo = "BAR" %}

{% extends "parent.html" with [some_string => foo] %}Parent

By using the parent tag, you can include the parent block's contents inside

the child block:

{% block child %}

{% parent %}

{% endblock %}Using the parent tag anywhere outside a block or inside a macro is a syntax

error.

Macro

Macros are a great way to make flexible and reusable partial templates:

{% macro bolder(text) %}

<b>{{ text }}</b>

{% endmacro %}To call them:

{{ @bolder("this is great!") }}Macro calls are prepended with the @ character. This is done to avoid name

collisions with helpers, method calls and attribute access.

All parameters are optional; they default to null while extra positional

arguments passed are ignored. Flow lets you define a custom default value for

each parameter:

{% macro bolder(text="this is a bold text!") %}

<b>{{ text }}</b>

{% endmacro %}You can also use named arguments:

{{ @bolder(text="this is a text") }}Extra named arguments overwrite positional arguments with the same name and

previous named arguments with the same name. The parentheses are optional only

if there are no arguments passed. Parameters and variables declared inside

macros with the set construct are local to the macro and will cease to exist

once the macro returns.

Macros are dynamically scoped. They inherit the calling context:

{% macro greet %}

<p>{{ "Hello," .. name }}</p>

{% endmacro %}

{% set name = "Joe" %}

{{ @greet }}The above will print:

<p>Hello Joe</p>The calling context is masked by the arguments and the default parameter values.

The output of macros are by default unescaped, regardless of what the current

autoescape setting is. To escape the output, you must explicitly apply the

escape or e filter. Macro calls that are used as part of an expression will

be escaped depending on the current autoescape setting. Inside the macros

themselves, escaping works as usual and depends on the current autoescape

settings. Undefined macros returns null when called.

Macros are inherited by extending templates and at the same time overrides other macros with the same name in parent templates.

Defining macros inside blocks or other macros is a syntax error. Redefining macros in a template is also a syntax error.

Importing macros

It's best to group macros in templates like you would functions in modules or classes. To use macros defined in another template, simply import them:

{% import "path/to/form_macros.html" as form %}All imported macros must be aliased using the as keyword. To call an imported

macro, simply prepend the macro name with the alias followed by a dot:

{{ @form.text_input }}Imported macros are inherited by extending templates and at the same time overrides other imported macros with the same alias and name pair in parent templates.

Decorating macros

You can decorate macros by importing them first:

{# this is in "macro_A.html" #}

{% macro emphasize(text) %}<b>{{ text }}</b>{% endmacro %}

{# this is in "macro_B.html" #}

{% import "macro_A.html" as A %}

{% macro emphasize(text) %}<i>{{ @A.emphasize(text) }}</i>{% endmacro %}

{# this is in "template_C.html" #}

{% import "macro_B.html" as B %}

Emphasized text: {{ @B.emphasize("this is pretty cool!") }}The above when rendered will yield:

Emphasized text: <i><b>this is pretty cool!</b></i>Include

Use the include tag to include bits and pieces of templates in your template:

{% include "path/to/sidebar.html" if page.sidebar %}This is useful for things like headers, sidebars and footers. Including non-existing or non-readable templates is a runtime error. Note that there are no mechanisms to prevent circular inclusion of templates, although there is a PHP runtime limit on recursion: either the allowed memory allocation size is reached, thereby producing a fatal runtime error, or the number of maximum nesting level is reached, if you're using xdebug.

Parameterized template inclusion

As with template extension, you can pass an array as the overriding context for the included template:

{% include "footer.html" with ['year' => current_year] %}The array parameter will override any variables in the current context but only for the duration of the include.

Path resolution

Paths referenced in extends, include, and import tags can either be

absolute from the specified source option when instantiating the loader

object, or relative to the current template's directory.

Absolute paths

Absolute paths must begin with a / character like so:

{% include "/foo/bar.html" %}In the example above, if the source directory is /var/www/templates, then

the tag will try to include the template /var/www/templates/foo/bar.html

regardless of what the current template's directory is.

Relative paths

Relative paths must not begin with a / character:

{% include "far.html" %}In this example, if the source directory is /var/www/templates, and the

current template's directory is boo, relative to the source, then the tag

will try to include the template /var/www/templates/boo/far.html.

Path injection prevention

Flow throws a RuntimeException if you try to load any file that is outside the

source directory.

Loading templates from other sources

Sometimes you need to load templates from a database or even string arrays. This

is possible in Flow by simply passing an object of a class that implements the

Flow\Adapter interface to the adapter option of the Loader constructor.

The Flow\Adapter interface declares three methods:

isReadable($path): Determines whether the path is readable or not.lastModified($path): Returns the last modified time of the path.getContents($path): Returns the contents of the given path.

The source option given in the Loader constructor still determines if a

template is valid; i.e., whether the template can logically be found in the

source directory.

Below is an example of implementing a Flow adapter to string arrays:

The above will compile the templates and render the following:

Output escaping

You can escape data to be printed out by using the escape or its alias e

filter. Output escaping assumes HTML output.

Using autoescape

Use the auto escape facility if you want all expression output to be escaped before printing, minimizing potential XSS attacks:

{% autoescape on %}Think of autoescape as implicitly putting an escape or e filter on every

expression output. You would normally want to put this directive somewhere near

the top of your template. Autoescape works on a per template basis; it is never

inherited, included, or imported from other templates.

You do not need to worry if you accidentally double escape a variable. All data

already escaped will not be autoescaped; note that this is only applicable

when escape or its alias e is used as a filter and not a function:

{% autoescape on %}

{{ "Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde" | escape }}You can turn autoescape off at any time by simply setting it to off:

{% autoescape off %}You can isolate the effects of autoescape, whether it's on or off, by enclosing

it with a corresponding endautoescape tag:

{% autoescape on %}

This section is specifically autoescaped: {{ "<b>bold</b>" }}

{% endautoescape %}By default, autoescape is initially set to off.

Raw filter

By using the raw filter on a variable output, the data will not be escaped

regardless of any escape filters or the current autoescape status. You must

use it as a filter; the raw helper is not available as a function.

Controlling whitespace

When you're writing a template for a certain file format that is sensitive

to whitespace, you can use {%- and -%} in place of the normal opening and

closing block tags to suppress whitespaces before and after the block tags,

respectively. You can use either one or both at the same time depending on

your needs. The {{- and -}} delimiters are also available for expression

output tags, while the {#- and -#} delimiters are available for comment

tags.

The following is a demonstration of whitespace control:

<ul>

{%- for user in ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"] -%}

<li>{{ user }}</li>

{%- endfor -%}

</ul>Which will yield a compact

<ul>

<li>Alice</li>

<li>Bob</li>

<li>Charlie</li>

</ul>While the same example, this time without any white-space control:

<ul>

{% for user in ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"] %}

<li>{{ user }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>Will yield the rather sparse

<ul>

<li>Alice</li>

<li>Bob</li>

<li>Charlie</li>

</ul>The semantics are as follows:

-

{%-,{{-, and{#-delimiters will remove all whitespace to their left up to but not including the first newline it encounters. -%},-}}, and-#}delimiters will remove all whitespace to their right up to and including the first newline it encounters.

The spaceless template tag:

Result:

Raw output

Sometimes you need to output raw blocks of text, as in the case of code. You can use the raw tag:

{% raw %}

I'm inside a raw tag

{% this will be printed as is. %}

{% endraw %}License

Flow is released under the MIT License.

Acknowledgment

Flow is heavily based on the original Twig implementation by Armin Ronacher and subsequently influenced by Jinja2, Fabien Potencier's Twig fork, Python, and Ruby.